In addition to the enormous adventure that was getting to shadow Yo-Yo Ma and Silk Road Ensemble on their Asia tour, my last two weeks was full of interesting highlights, including briefly putting myself on the Shanghai marriage market, having my fortune told at China's equivalent of the Oracle of Delphi, concocting new plans for my Watson project, and of course seeing good friends over amazing food.

During the Silk Road tour, the players got a day off in Shanghai. Nick wanted to walk around the city and wasn’t keen to spend the day in museums, so I suggested something far more interesting—checking out the Shanghai marriage market. I had read that Shanghai parents congregate for hours every weekend in People’s Park with signs advertising their unwed children, and was eager to see this manifestation of China’s gender imbalance. Nick was incredulous—how interesting could a public park full of desperate Chinese parents trying to match up their eligible but rapidly aging sons and daughter be?—but agreed to humor me so I could see what the fuss was all about.

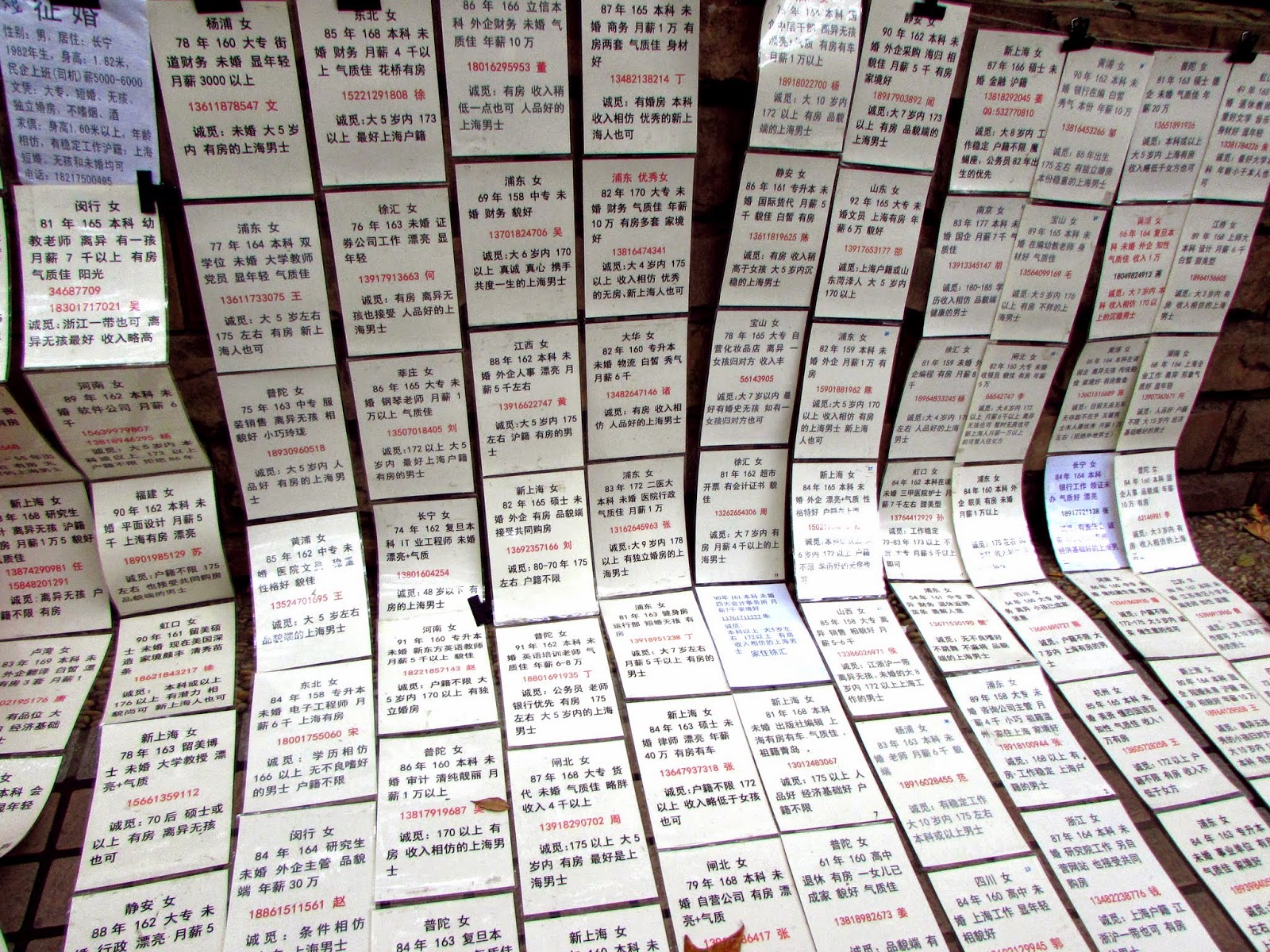

We got to the park and were immediately blown away—this wasn’t the handful of people we had imagined, but rather thousands of parents with signs listing their child’s age, education, occupation, height, salary, whether or not they had a car and an apartment, and the qualities they were seeking in a potential mate. There were also matchmakers, or perhaps match brokers, who sat in front of dozens of signs while offering consultations. There were far more daughters being advertised, and most seemed to be in their thirties or later. (This is reflective of the social stigmas surrounding “leftover women,” or women are over age twenty-eight and still single.) One mother told me she had been at the park advertising her daughter every Saturday and Sunday for the last few months (much to her daughter’s dismay) saying that the daughter works too hard to date and doesn’t have friends who can set her up.

I was reading some of the advertisements and translating them for Nick when an elderly woman with a mouth full of silver teeth and a floppy hat came up to me and started asking me if I was looking as well.

“Yes, I am!” I figure it’s good to always keep my options open.

Almost immediately a flock of middle-aged Chinese women surrounded me, complimenting me on my Chinese and my appearance and asking me how old I was.

“You are too young for this!” they exclaimed after I told them I am twenty-one.

“Oh really? Well, I’m just looking.”

“I will show you some pictures!” The old lady pulled out an envelope of photos of a non-descript young man on a dock.

“Is this your son?”

She didn’t answer, but instead said, “Isn’t he so handsome?”

“Oh yes, but why isn’t he married? Is something wrong with his personality?”

“Oh no, he’s a very happy boy!”

In the blink of an eye the seemingly frail old woman had linked arms with me and was dragging me through the crowd while dialing her phone, ostensibly to connect me with some potential matches. I decided that this would be a good point to make a swift exit before I broke too many hearts, and Nick (who had been observing all of this from a safe distance) and I dashed off while her back was turned. I looked back to see her surprised and disappointed expression from afar, and waved goodbye while trying to make the international sign for “It’s not you, it’s me!”

The rest of the day was really lovely as well—we walked through the French Concession, a well-shaded series of streets home to many niche boutiques and chic cafes. We stopped in a Dutch designer’s store and I briefly dusted off my Japanese to talk with the store attendant (who said I was the first foreigner he’d met who could speak Japanese) and went to a violin shop and talked with a teenaged violinist and her overeager stage mom about studying music in the U.S. We also stumbled upon the underground Shanghai Propaganda Museum (which I visited last time I was in Shanghai), and I had a chance to rave to the gallery owner about how much I love the exhibit. After I told him that we are musicians, he pulled out a flute inscribed with Mao’s quotations, and another one he cavalierly threw down on the table. (“This one's from the Qing Dynasty.”)

In Shanghai I also got to hang out with my good friend Helen, who took me out for the city's best xiaolongbao, curry soup, and shengjian mantou. We met about a month ago in Urumqi, where Helen was wrapping up a Fulbright year following a year of learning Chinese in Chengdu and the Tibetan grasslands while working in a Chinese restaurant. She’s absolutely amazing—we haven’t known each other for long but I feel like we have been best friends for our entire lives. We really enjoy wearing matching clothing and jewelry; for instance, we both have bracelets from Urumqi that ward off the evil eye. In Shanghai we stocked up on matching earrings with the Chinese character 囧, which is used an emoticon to express embarrassment, and also got blouses from an ethnic minority clothing stall. The latter have special significance because in Urumqi (and around China generally) people would frequently ask us, “What ethnic minority are you?” or assume we are Russians (often a euphemism for prostitutes). Even the guy who sold us the shirts was way off when guessing our nationality—to be fair, “Belize” was really not a terrific guess on his part. In any case, that evening we proudly donned our new “ethnic” attire, came up with an elaborate fake back story about our minority origins, and planned to play our Uyghur instruments (Helen plays tambur, which is a plucked long-necked lute-like instrument) in People’s Park and totally confuse all passerby. We also planned to go to a dance club in our garb and do Uyghur dancing. (Sadly, neither plan came to fruition due to my long afternoon nap, and then us forgetting the address of the dance club after we had set out. We’re postponing until next time.)

I also saw my friend Yuting, who was a year ahead of me at Wellesley and just moved to Shanghai a few weeks ago to launch an organic baby food delivery service, the first of its kind in China. Baby food is a sensitive subject and hot item in China because of the 2008 scandal in which melamine, a chemical in plastics and fertilizer, was found to have tainted milk powder and poisoned hundreds of thousands of infants (fatally, in at least six cases). I remember Yuting telling me two years ago, right before she graduated, that her dream was to study and improve food safety in China; now, I am so impressed that she is following through with this dream and addressing the very real need for trustworthy and high-quality baby food in China. When I saw her in Shanghai, she had been in the city for all of a week and was already going from meeting to meeting, talking with industry leaders, government officials, and potential angel investors. “This is just a stepping stone,” she said. “Once this company is started and going well, I’m going to move on. I’m really interested in focusing on sustainable energy in China.” I’m convinced she’s going to save the world.

I parted ways with Helen and Yuting (who I hope to see again before I leave China) and took a fourteen-hour overnight train to Xian, where my close friend and another Wellesley classmate Christine, who is researching waste management on a Fulbright in villages outside of the city. She’s particularly interested in biohazardous waste management—many villagers have no means to properly dispose of waste from medical clinics, for instance, and throw used needles and empty blood packets into the river. To quote Christine, “It’s a major health disaster waiting to happen.” She is having a blast with her work and life in Xian, and while she may be far from home is hardly missing her family—her parents have been staying in Xian as well for the last month or so and using Christine as a home base while they tour around China. They were there when I visited and were overwhelmingly kind to me—her mom did my laundry, her dad took us around the scenic spots of Xian, and both of her parents constantly stuffed us full of food.

As I haven’t seen my family for four months and will be away from home until summer of next year, some family R&R time was exactly what I needed. And, for a those few days it was like my own parents were actually there: her mom lectured me that I should stop running around the world and going to dangerous places, while her dad bragged about my accomplishments to everyone we encountered. I was truly touched when he declared, “You are Christine’s friend and classmate, and Christine is our daughter, so we consider you to be our daughter as well.” After two weeks of traveling and months of going it on my own, their parental love came at just the right moment.

(brief interlude for photos of the Xian sights)

As I haven’t seen my family for four months and will be away from home until summer of next year, some family R&R time was exactly what I needed. And, for a those few days it was like my own parents were actually there: her mom lectured me that I should stop running around the world and going to dangerous places, while her dad bragged about my accomplishments to everyone we encountered. I was truly touched when he declared, “You are Christine’s friend and classmate, and Christine is our daughter, so we consider you to be our daughter as well.” After two weeks of traveling and months of going it on my own, their parental love came at just the right moment.

(brief interlude for photos of the Xian sights)

|

| Dowager Empress Cixi, last empress of China, apparently did the calligraphy on this rock |

|

| Chiang Kai-shek, wearing only pajamas, hid from arrest in this crevice (Christine's photo) |

|

| Imperial bathhouses in the middle of the city |

|

| These terracotta warriors look like they will be cold in winter |

|

| I was surprised to discover that most of the terracotta warriors are in the excavation process or still entirely buried |

|

| Huiminjie (Hui Minority Street) |

In addition to seeing the terracotta warriors, Mount Li, and Huiminjie (the Hui minority street, which is full of food and craft stalls), Christine and her dad and I went to a temple we were told Mao Zedong and Chiang Kai-shek had gone to have their fortunes told. For 10 RMB (under $2) it seemed like a no-brainer to also have our fortunes told (at least to Christine’s dad and me—Christine herself was skeptical and elected to roll her eyes at us). We kneeled at the altar, did some bowing, and selected a numbered stick from a bucket. The number correlated to a piece of red paper with a fortune written in old Chinese, which we asked the temple fortune teller, an old man with gnarly hands, a top knot, and a thick accent, to interpret for us. He asked me my day and time of birth, and proceeded to do a seemingly complex set of numerological calculations, and then told me something to the effect of:

“You are generally healthy but you need to be careful of your 胃 [wei, traditional Chinese medicine term associated with the stomach]. You need more earth and water in your life. Your hands are cold in the winter.”

At this point I was very incredulous—aren't everyone’s hands cold in the winter? But Christine and her dad clarified that he was meant that my hands are frigid at all times in cold weather, which is not something everyone experiences (and in my case, is true). The fortune teller went on:

“You are a good person, but between the ages of twenty-four and thirty-six you need to protect yourself and be careful of the people you trust—watch out for wolves around you. Your career will be very successful, but not your marriage.”

Christine’s dad was told that he was a worrier and apparently got a less-than-stellar fortune as well. We were told, however, that for a fee, we could burn our fortunes and make them go away. The temple staff showed us the donation books from others trying to avoid destiny, and saw donations averaged between 100 and 200 RMB. Quickly our attempt to learn our fortunes was turning into a veritable investment to trick fate. Feeling the pressure, Christine’s dad and I chipped in 100 RMB between the two of us (“Don’t tell Christine’s mother,” he said), received red ribbons to tie around the temple courtyard, and descended from the altar to go burn our fortunes. We quickly realized we needed a way to burn our fortunes, and looked towards the piles of already-smoking incense. And then we heard: “You can’t use someone else’s incense to burn your own fortune!” Of course one had to buy incense (for another couple hundred RMB)—at that point we hoped frugality was a virtue that would outweigh whatever misfortunes would come our way, and left the temple still clutching our red papers.

(interlude for temple photos)

I had been complaining to Christine about the things that had been making it difficult for me to adapt to life in Urumqi, including the food, climate, bureaucracy, and methods of music teaching. More than anything, I was frustrated that I had spent nearly a month in Urumqi with little to show in terms of musical progress or a solid network. I have mentioned before, it has been a struggle to figure out how things work on a daily basis in Urumqi; in terms of learning Uyghur music, the conservatory approach here prioritizes rote learning and adherence to a written score that makes it difficult to actually acquire or intuit the wèidào, the inherent flavor of the music—in fact, at times it seems like this is being totally suppressed. Additionally, connecting with the community at the Arts Institute hasn't really gone as planned. I have some Han Chinese pals who view me as a token American friend (kind of a status symbol—not a terrific basis for a meaningful friendship), some lovely friends who are expat researchers, and Uyghur acquaintances who I know through them. I have learned a lot merely through getting to know them, but ultimately I feel like a fly on the wall rather than a participant in the musical community.

Solution-minded as she is, Christine didn't just sympathize with my concerns but also took it upon herself to reach out to her friends and acquaintances in Xian to ask about musicians with whom I could connect. In a matter of hours, she had tracked down multiple students at the Xian Conservatory of Music, one of China's top music schools, to meet with us. Early the next morning, Christine and her parents and friends and I set off to go take a tour the conservatory with a few current students, including an opera singer, a guzheng player, and erhu player who had recently come in second place in a national competition and is excited by the prospect of teaching me. They showed us around the campus, gave us an impromptu concert (and had me play as well), and took us out for a delicious lunch. Christine also found Zhang Zhang, a faculty composer who is willing to sponsor me, arrange my housing in Xian, and give me a job teaching violin at his non-profit music school. "Just go back to Urumqi, grab your stuff, and come back here right away! Why do you need to be miserable in Urumqi?" I was struck by their kindness and generosity to all of us, especially me, a total stranger—it is sort of amusing that midwestern hospitality is a concept that pervades China as well!

I leave at the end of this week—I will be leaving with the knowledge that I have learned so much from my time in Urumqi, and that there is so much more that remains to be understood.

“You are generally healthy but you need to be careful of your 胃 [wei, traditional Chinese medicine term associated with the stomach]. You need more earth and water in your life. Your hands are cold in the winter.”

At this point I was very incredulous—aren't everyone’s hands cold in the winter? But Christine and her dad clarified that he was meant that my hands are frigid at all times in cold weather, which is not something everyone experiences (and in my case, is true). The fortune teller went on:

“You are a good person, but between the ages of twenty-four and thirty-six you need to protect yourself and be careful of the people you trust—watch out for wolves around you. Your career will be very successful, but not your marriage.”

Christine’s dad was told that he was a worrier and apparently got a less-than-stellar fortune as well. We were told, however, that for a fee, we could burn our fortunes and make them go away. The temple staff showed us the donation books from others trying to avoid destiny, and saw donations averaged between 100 and 200 RMB. Quickly our attempt to learn our fortunes was turning into a veritable investment to trick fate. Feeling the pressure, Christine’s dad and I chipped in 100 RMB between the two of us (“Don’t tell Christine’s mother,” he said), received red ribbons to tie around the temple courtyard, and descended from the altar to go burn our fortunes. We quickly realized we needed a way to burn our fortunes, and looked towards the piles of already-smoking incense. And then we heard: “You can’t use someone else’s incense to burn your own fortune!” Of course one had to buy incense (for another couple hundred RMB)—at that point we hoped frugality was a virtue that would outweigh whatever misfortunes would come our way, and left the temple still clutching our red papers.

(interlude for temple photos)

|

| Lamenting the fortune telling racket (Christine's photo) |

|

| With Christine outside the temple complex (Christine's photo) |

|

| Where we didn't burn our fortunes after all |

|

| Lunch with Christine, her parents and friends, and Xian Conservatory students (Christine's photo) |

.jpg) |

| (Christine's photo) |

|

| Erhu and guzheng students jamming out at Xian Conservatory |

I had initial misgivings about abandoning my self-assigned post in Urumqi; however, this opportunity is really amazing on many levels, and I have come to realize that another month or so in Urumqi would not be as productive or enjoyable as a month in Xian. It's not that I expect to be playing in ensemble rehearsals (though that would be great), but I feel like there are various cultural, linguistic, and logistical barriers that prevent me from even being an active observer of music culture here. It certainly is not an overall impossibility, but I have come to realize that achieving the kind of connection with people and music here for which I strive is going to take time I currently have. It's not that I expect to waltz in and know what's going on and immediately have complete linguistic, cultural, and musical faculty, but in this case I believe that the steps I can make toward that point of understanding in the next few weeks will be far larger in Xian than in Urumqi.

I leave at the end of this week—I will be leaving with the knowledge that I have learned so much from my time in Urumqi, and that there is so much more that remains to be understood.